Our new energy system will be a mosaic of large and small projects, and one venture Zero West has helped get off the ground is a great example of how the small stuff will work.

The Microgrid Foundry is a joint venture set up in collaboration with Bristol based renewable experts Clean Energy Prospector (CEPRO) and three community energy companies to push ahead with a new model for supplying all the energy a household needs.

What’s a microgrid?

Like the more familiar national grid, a microgrid is a set of electrical installations linked by connectors and operated together (more on this below). In this case, microgrids will function to even out supply and demand in a house or flat that uses electricity, mostly self-generated, for power and heat. The government announced in the Spring budget statement that gas heating will be excluded from all new-build homes from 2025. Microgrids are one way this can be done.

In this case, the plan is to work with developers building a clutch of new homes, ideally at least 50. Each will be set up as a self-contained community energy supplier, with a private network using solar electricity generation, air and ground source heat pumps, and battery storage packs.

The projects.

There are three schemes on the blocks: the smallest (33 homes) is a self-build project under way in Kings Weston with Bristol developer Bright Green Futures.

Then there is a 54 home project in Bridport in Dorset,

and a somewhat larger (104 dwellings) development in Milton Keynes.

These are all at or near the scale where it becomes more feasible to finance the microgrid kit. And working on all three together allows shared learning between the projects, bujilding on CEPRO’s experience with a pilot project in Bristol. “We first put a grid scale battery in a car park on a housing estate in Winchester”, says CEPRO co-founder Damon Rand, “then we worked out how to link it to solar panels”.

They have been working with Zero West for the last 18 months to organise the move to the next stage, and the MicroGrid Foundry Joint Venture was launched early in 2019. Microgrids need patient investors, and the initial partners are all community interest companies – Bristol energy Co-op, Wolverton Community Energy and Chelwood Community Energy. The initial investment amounts to £200k, which will cover the planning and design of the microgrids. The entire scheme is forecast to cost the Foundry £1.6m, and there will be a further call for investment later this year or early in 2020.

Once the houses and flats are occupied, and the microgrid is operating profitably, the plan provides for site’s Housing Association, Land Trust or Residents Management Company to buy out the Foundry stake in the microgrid. So there’s a social as well as technical side to the project, calling for work alongside people who – like most of us – are probably looking for electricity at the press of a switch, a warm house, and a simple, affordable bill every month or quarter. Making all that work smoothly will be part of the challenge, and CEPRO will be taking on people to work with residents as well as more engineers over the next year, says Rand.

Grids large and small

In the bigger picture, microgrids are set to be a key feature of a reorganised energy system. Distributed solar, heat pumps and storage can bring clear benefits to local grids, but valuing them at the at the national level isn’t nearly settled yet. So taking local control of local grids is one way we can bridge the renewables finance gap without waiting for government, says Rand: “We could have done this years ago but for the financing – but the government isn’t really supporting renewables”. As a result, “we’re drawing a boundary round our sites and sharing the energy among our communities”.

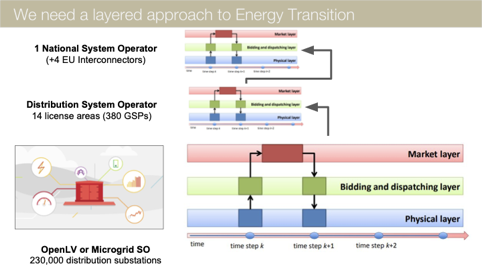

Soon, though, distributed renewable generation and microgrids will have to be integrated with the larger system. That’s complex because it cuts across the organisation of our electricity system in developed nations.

To get where we are now, we built massive, centralised generating plants – coal at first, then gas, and some nuclear or linked to dams – because they were the cheapest and most efficient way to make electricity. Then the power is transferred to where it is needed by a network of high voltage lines, above or below ground.

It was a colossal feat of planning and engineering, especially in big countries like the US – which has 160,000 miles of high voltage power lines. But a world where homes can make and store their own electricity, at least some of the time, looks different. Conceptually the system could look more like this.

The shorthand for how it will work is usually that we’ll build a “smart grid”. That will reap the benefits of a more widely distributed energy system, help smooth out the fluctuations in supply and demand that make some doubtful about renewable energy sources, and improve efficiency in ways that reduce peak demand significantly.

The overall goal is clear. In the UK, the National Grid, which is doing some admirably hard thinking about its future operation, has just reported how it envisages a zero carbon power system by 2025.

Their outline of how that might actually work gets pretty technical, pretty quickly. But it’s clear the new system will be more complex, with more components that operate on different scales, more intricately interconnected. Some will rely on IT, in the form of “virtual power stations”. But many will rely on physical connections – microgrids. And that is what this project will demonstrate in action on a scale that can make a real impact.

Read more about the MicroGrid Foundry here (pdf)

(With thanks to Damon Rand for comments)